Better Than Feedback

The year was 1999 when [Kent Beck](https://www.kentbeck.com) introduced what seemed then (and still does) a radical idea: What if software developers work in pairs? Imagine it. You have a team of, let’s say, ten developers that work in pairs, each pair on a single task at a time. This means your team can do only five things in parallel instead of ten. Your team’s productivity will be down by 50%! Or will it?

The premise (and promise) of Extreme Programming (XP) was that the team would be more productive and create higher-quality software by working in pairs. The magic that enables this improvement lies in shortening the feedback loop to practically zero.

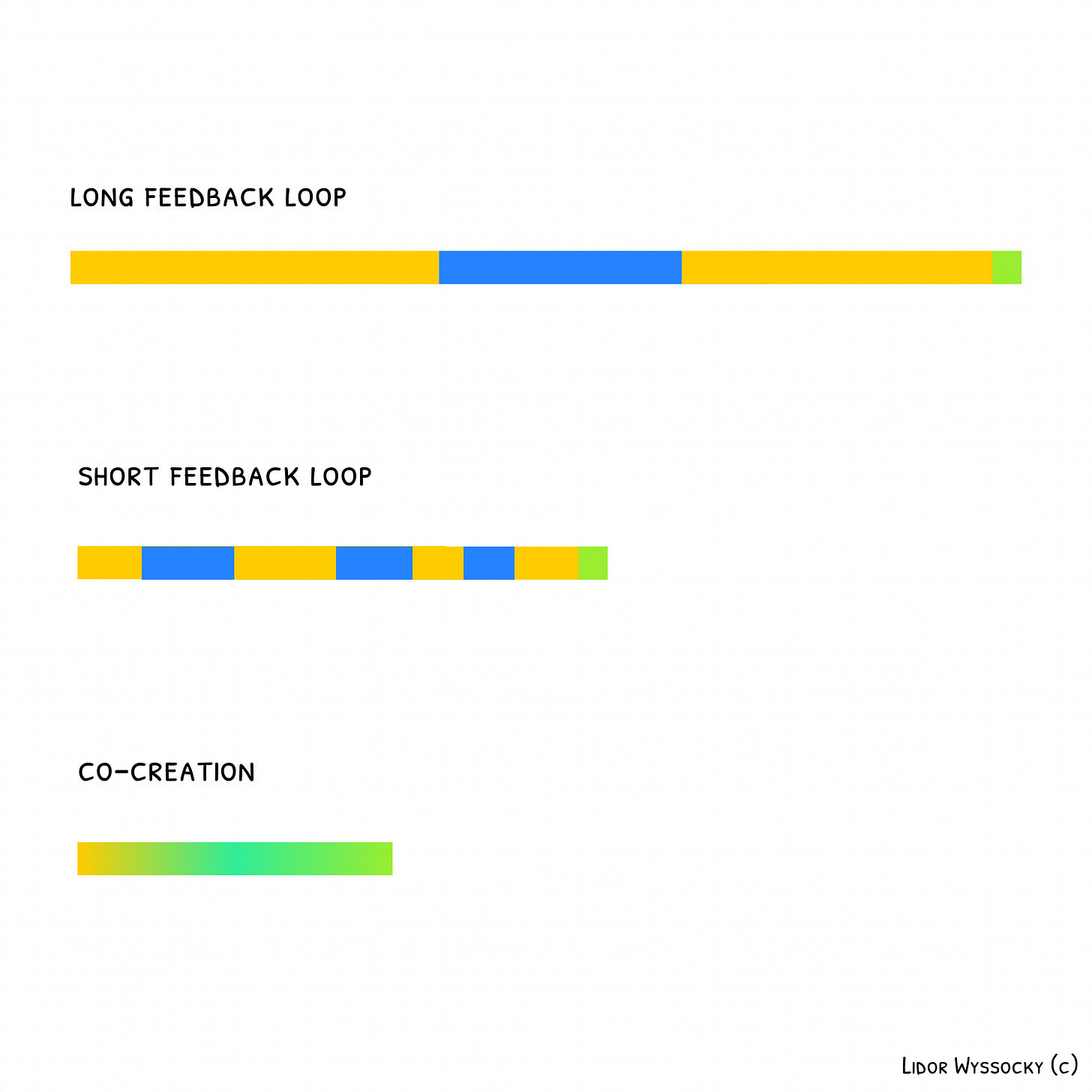

Feedback is essential. Without feedback, we can never know if what we produce has value. Traditionally, the feedback for software developers came in the form of testing the code. But here is the thing: the longer you wait for feedback and the more work you produce before receiving feedback, the less effective you are. There’s a greater chance you are missing something and, as a result, advancing in the wrong direction. The longer it takes to identify a mistake, the harder and more costly it is to fix it.

That’s how the concept of code reviews came to be. Developers can review each other's code instead of waiting until it is tested. You don’t have to code a complete feature or something the testing team can work with. A second pair of eyes can find at least some mistakes before investing in formal testing. Reviewing the actual code, not just what it appears to accomplish, also enables the developers to find errors or opportunities for improvement that are practically unreachable in traditional testing. You can often prevent future mistakes by verifying the code is written clearly.

All that was given when Kent Beck came up with his simple idea: shorten the time between creating something and reviewing it to zero. Instead of working even one day before someone highlights a mistake or an opportunity for improvement, he created a setup where feedback flows naturally all the time. You always have a second pair of eyes right there as you do your work.

Of course, when you try this setup, you soon realize the line between who does the work and who reviews it blurs. At some point, both colleagues switch roles without even announcing it. When one person writes, the other is there to consult her until they switch roles. It happens naturally and as frequently as needed. They work as a team.

XP is an extreme (obviously) example of the importance of feedback and the opportunity that lies in making it immediate. It also sets the ground for a broader idea we can apply beyond writing code: Co-creation is a setup enabling constant, immediate feedback.

In many business processes, some of the work is synchronous by default. A Product Manager might develop the draft of the specification for a new feature, but once they hand it over to the development and testing team, it could become apparent that the requirements are ambiguous or not feasible. One team might create a plan but when other stakeholders review it, they realize that some underlying assumptions are incorrect. The IT team might plan a major upgrade of some information systems, but when it is brought to discussion, the users of this system raise valid concerns that must be addressed.

All these examples underscore the importance of feedback. These processes include predefined junctions where feedback is collected, enabling us to improve what we create in the next iteration. However, just like the case with Extreme Programming, shortening the feedback cycle can increase both productivity and quality. Sometimes, we can shorten this cycle to zero by moving from a create-review-fix mode to a co-creation mode.

The more involved developers and the testers are in writing the requirements, the shorter the feedback cycle is. The Product Manager still leads the work, but the work could be done in tiny iterations or, even better, as a group. If instead of creating parts of a plan and trying to stitch them together after the fact, all teams develop the plan together, issues will be raised and addressed in real-time and not later down the process. When planning the upgrade of the information system is done with representatives of different user groups, there is a good chance the team will get it right the first time instead of doing multiple iterations until everyone approves the plan.

Of course, assembling all the relevant stakeholders to work together as a team on every task is neither realistic nor necessary. Nevertheless, co-creating can turn into a great opportunity when the potential for back-and-forth is high or when there is a lot of friction in handing over a work product from one group to another.

It might sound like excessive overhead: “Why assemble four, five, or six people when one person can perform the task?” But just like the XP experiment showed, there are cases where doing the work together reduces the overall time spent on the task while increasing the quality of the outcome.

Unleash the power of Generative Communication and turn it into your superpower. I lead Generative Communication and Content-Shaping workshops and talks for teams and organizations.

With 1:1 mentoring, I help individuals communicate better, write better, and turn their ideas into an impact.

Drop me a message…