When we think of data in the context of organizational decision-making, we tend to focus on numbers. In most organizations, this data is the most accessible. We have so many systems with hard data that is easy to quantify, and the more we collect, process, and play with it, the more we believe we understand the terrain and can come up with accurate insights.

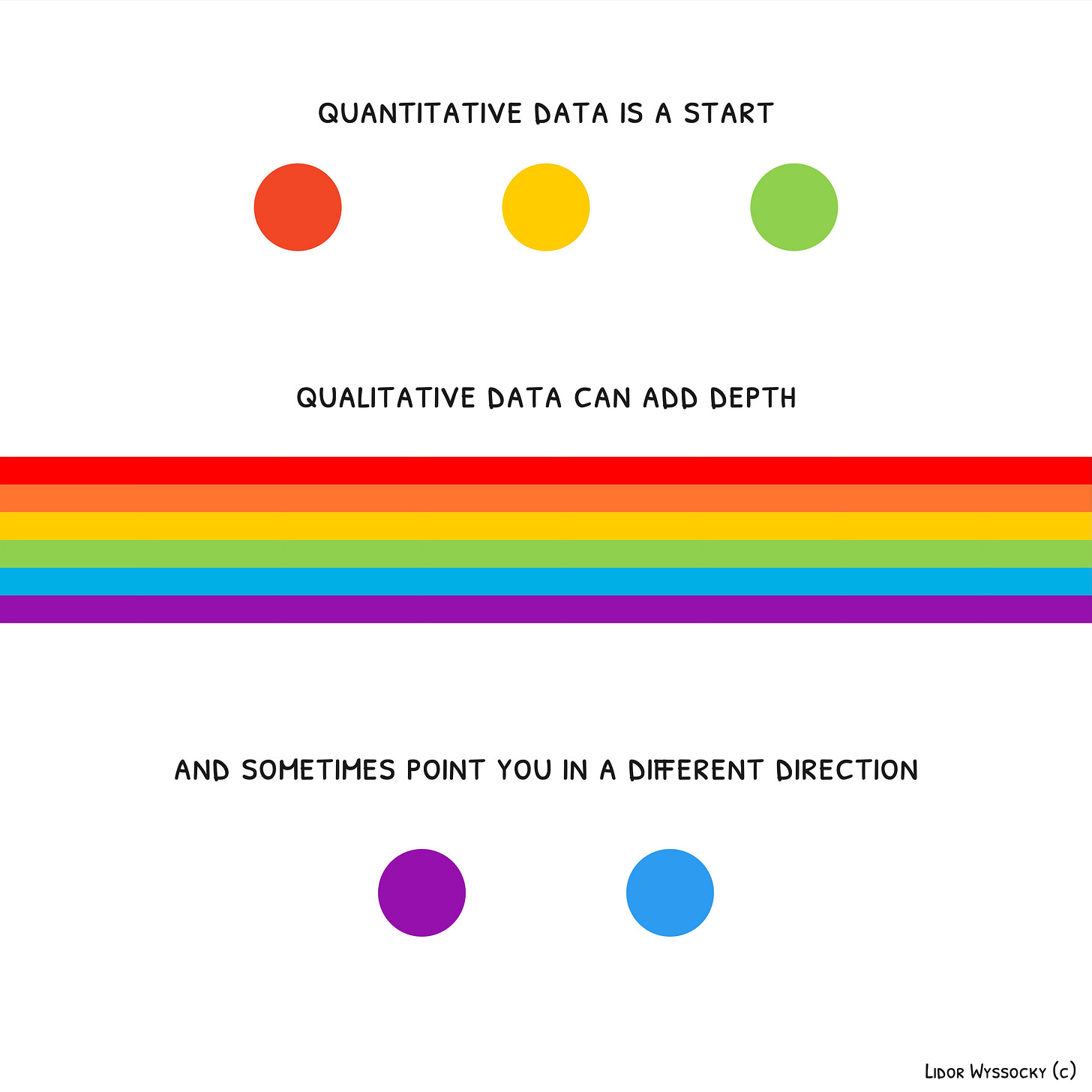

Hard, quantitative data is essential. But it is rarely enough to gain a deep understanding of the challenges we face and how to address them. When we communicate exclusively using charts and tables, we will always miss essential pieces of the picture.

When you analyze quantitative data and see a drop in sales, for example, it is a good indicator that something is happening — something that requires further analysis. If you have additional numeric data to work with, that’s great, but there’s more you can do to get a profound (sometimes completely different) understanding of what’s happening and what to do next.

Talking directly with the salespeople could shed new light on where they struggle and what happens in the field that results in fewer sales. Interviews with potential customers are another possible source of information, as is analysis of the competition in areas where sales have dropped.

Making a decision or even setting a target without getting this “softer” data will often result in suboptimal actions. It can even result in making a decision that will make things worse. Qualitative data can add hues, whereas quantitative analysis pushes us to see things in black and white. This is not to say that quantitative data is not critical. If nothing else, it can point us to areas where we need further analysis. At the same time, we must be aware of the potential blind spots numeric data can create. No matter how well-designed our quantitative data is, it is impossible to think in advance and collect data on every dimension that can potentially affect our decisions.

Qualitative data requires some legwork. It will not magically appear from within your information systems, which might be why it is neglected in many business cases. There are ways to quantify qualitative data so it can be added natively to the reports and dashboards we already have, but acquiring this type of data requires us to communicate effectively first.

Qualitative data is not free of challenges. By definition, it can be subjective, and scaling its collection and analysis is not trivial. How much to invest in collecting qualitative data and how to take into account its inherent flaws are important aspects you’d have to experiment with. But the fact that this kind of data introduces its own challenges doesn’t dismiss its value.

Without talking to the people involved in whatever aspect we are analyzing — the people who have a real sense of what’s going on, even if only from their local perspective — we can’t hope to gain a real understanding of what we are facing, no matter how much hard data we have to work with.

There are questions numbers won’t be able to answer. There are questions we can’t even imagine when all we see are numbers.

Quantitative data may also be incomplete or inaccurate. Always ask those questions before starting to draw conclusions from quantitative data.